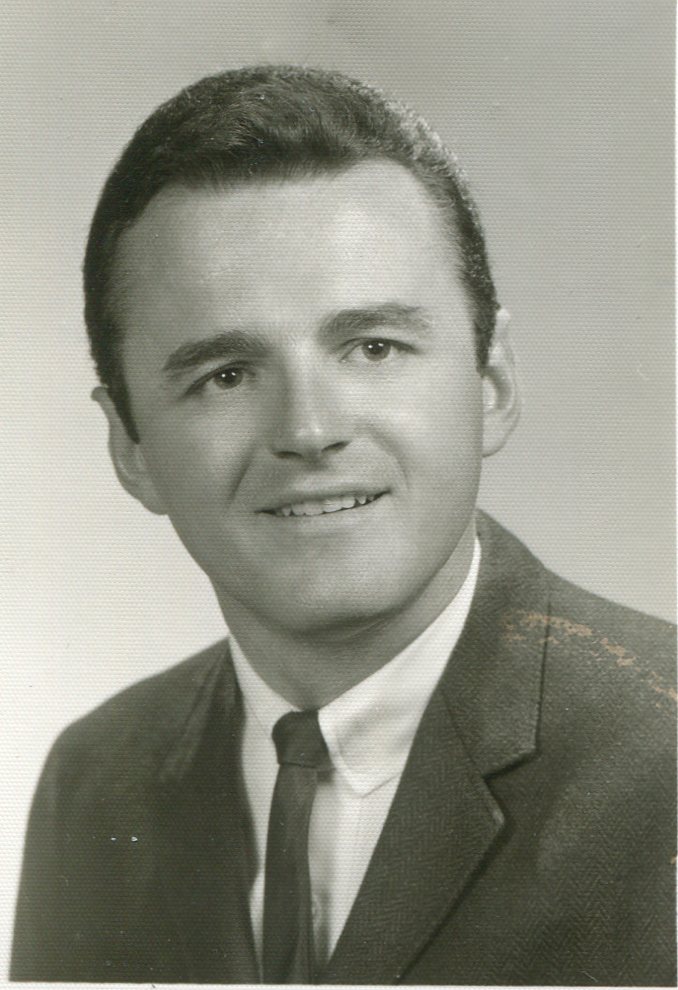

The George M. Pullman Educational Foundation helped Tom Meagher attend college. Now he’s giving back.

At age 70, Tom Meagher has the luxury of reviewing a life well lived—a loving family, a fulfilling career, a retirement characterized by good health and financial comfort. You get the feeling he wouldn’t change much if he had to do it over again.

It might have turned out differently. His father, a diabetic, died at 34, leaving Meagher’s mother to take care of 6-year-old Tom, his 8-year-old brother, and 2-year-old sister. The kids toughed it out in public schools near their home at 75th and Damen on Chicago’s South Side. The path of least resistance, when he graduated from Calumet High School in the early 1960s, would have been to get a blue-collar job, punch a clock, and contribute to the family budget. This could have been a fine life.

But Meagher, who liked math and science, had other ideas. He wanted a college degree. His mother encouraged him. His grandmother helped him complete applications. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign welcomed him aboard.

“In 1962 it was $135 per semester for in-state tuition and $450 for a semester in the dorm,” said Meagher. “So it was less than $1,200 a year for tuition and room and board.” Today, the cost of attending his alma mater is about $30,000.

Regardless, $1,200 was $1,200 more than the Meagher family could afford. “I don’t remember how we learned about the George M. Pullman Educational Foundation, but we applied and they granted me $700 annually,” he said. Like many Pullman Scholars, he covered the rest of his expenses by working part-time. And he threw himself into studying engineering mechanics.

During the school year, Meagher worked on campus in a research lab doing such things as studying crack detection in hard steels, especially at low temperatures. Then he had a variety of summer jobs, ranging from working on a surveying crew for the Belt Railway to counting auto traffic for the Illinois Department of Transportation.

Meagher worked in a factory during his last summer before college. “If ever I was in doubt about going to college, that experience fixed it,” he said. “It was miserable.”

Meagher maintained his Pullman Foundation Scholarship throughout his college years, during which time he met Joan, his wife-to-be, on a blind date. She became a Pullman Scholar, as well.

When, during his senior year, a professor took Meagher and other students to visit Caterpillar Inc.’s research facilities in Peoria, he figured the international equipment manufacturer would be a good place to work.

In 1967, Caterpillar offered him a job. Meagher proceeded to work there (mostly at facilities in suburban Chicago) for the next 41-plus years, until retiring in 2009.

“I loved it,” he said of his years at Caterpillar. He loves being retired, too, maintaining a strict exercise program at his house in the western suburbs of Chicago and traveling abroad, often with his daughter, a dean’s assistant at Waubonsee Community College in Sugar Grove, Illinois.

But for the last three years, Meagher has been doing something just as fulfilling—helping the Pullman Foundation interview scholarship candidates.

“For me, the value of the scholarship was incalculable,” he said. “No Pullman Scholarship, no U of I; no U of I, no Caterpillar. It was fortuitous that I got that scholarship.”

Now he’s giving back. “In a typical year the Foundation gets between 500 and 600 applicants,” he said. They winnow it down to about 200. From there, they reduce it to the final group who will receive annual awards.

In the aspiring Pullman Scholar applicants he reviews, he sees himself as a youth. It’s a reflection of the Foundation’s consistent mission over the last 65 years to ensure that academically gifted students of modest means have access to higher education.

“We alums have experience that’s invaluable if we can transfer it to kids and help them get up the ladder,” he said. “We’re linking experience to need.”